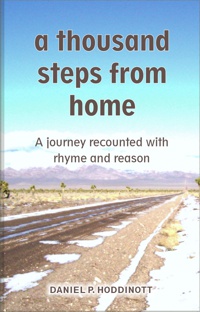

As I write this, my new poetry book, a thousand steps from home, is making its entrance into the world. With apologies to women everywhere (the only ones qualified to truly testify to the extent of the physical travail), bringing this book project from point of inspiration to physical form has felt like going through the birthing process.

The experience of fretting over not just one creative piece but an entire collection of works is like no other literary endeavor. The challenges are many: creative flow, logistics and then crucial decisions at crossroads not anticipated when the project began.

A volume of poetry, much like a musical album, is actually a collection of creative expressions gathered together in one package for the purpose of developing a thematic whole. (At least this is what’s true for me when selecting parts for assembly.) The individual pieces don’t necessarily have a direct relationship to those abutting them (though in some cases they might), but neither are they random choices; they are all constituent parts of a greater whole, throughout which an identifiable theme persists.

Not lost on the exhausted poet in calculating the emotional toll afterward is that many of those constituent parts had been carefully crafted earlier as standalone works; now asked to surrender individual stature for the sake of becoming part of a collective, in which the statement that makes it great defers to one generated by process and not organic inspiration.

Done well, it most definitely is the thematic whole that carries the day. Whether it works is determined by the reader, not the author: Did you see yourself or your life experience reflected in some way as your eyes traveled across the span of pages?

In many of my major creative works, the overarching theme describes a journey, and many of the pieces are drawn from observations the traveling-man persona I develop would have been apt to make in the traversing of a stretch of land from one place to the next. It works that way on the Sighs of the Times CD as well.

Poetry is still the most honest form of written expression, as far as I’m concerned. A poet will knowingly enter into the grueling creative process for reasons other than commercial success, while most other writers calculate the financial return before setting pen to paper. Nor is the motivation limited to creating beautiful word objects, in the hopes of eliciting recognition for praiseworthy craftsmanship. While hope reigns eternal on both of those fronts, the poet is more likely to be moved by an irrepressible need to convey insight having been gained into aspects of the human condition, of injustice perpetrated on some innocent, of hope and longing, and perhaps even a realization that owes its dawning to the requisite number of hours spent in a long night, contemplating the color of despair.

The poet’s gift is not only keen and unusual observation tendencies, but also an ability to craft words in such a way that they ring as clearly and as eloquently as any musical instrument, with cadence that evokes a rhythmic response in the reader and a resonance that echoes in someone’s midnight hour. Insight is the poet’s stock in trade — gained by having experienced deeply on an emotional level.

This is why it can be said the poet’s muse is also his/her curse and his/her curse is also the poet’s muse.

Consider the labor of birthing every one of the individual poems that go into a collection. The visuals that spring to mind tell only part of the travail; there is also the requisite entering into one’s muse, and living the emotional reality of its essence, each and every time.

So why do we do it, when the material rewards are so evidently few? When stardom is available upon some other road? Because we believe, first of all, in the integrity of the observation, and that it is important for what we are writing about to find a voice.

We animate the inanimate so that the agitated may become still. We create spaces in the psyche where stillness and reflection can live — for a moment, an hour or a day — and insight can be realized.

The immediate voice the reader hears is the poet’s voice, and accommodation has to be made to hear it for what it is, not what you might wish it to be. The poet is the reporter sent into the field; what you read is a result of facts gathered, situations examined and interpretations made. The authenticity of the reporting going on in the delivery of a poem, then, is dependent upon the poet’s voice and his or her perspective being understood (though not dwelled upon). It is only then that other voices — those being freed from the silent place of invisibility and dismissal by the main stream flowing between the riverbanks that frame everyday life — can vibrate authentically and at audible frequencies.

When a tree falls in the forest, does anybody hear? Well, as far as I’m concerned it doesn’t matter, because some creature living in the vicinity, whose existence will be impacted by the event, surely will. Nor is the potency of concentrated wordcrafting such as poetry diminished by mainstream audiences being too removed from place to notice; those who do receive our words here are moved. And like the painting that whispers from the walls in the gallery, that is often enough.

Poets don’t believe in silent words, polite or otherwise. We believe in words that are determined to rise up and be heard every time some curious reader frees them by turning the page where they live.

There is no point in championing — nor defending, for that matter — the words that populate the pages of a thousand steps from home here. I’ve given them a voice in good faith, and empowered them with interpretation of observations made on an honest journey through contemporary society, so whether they succeed in telling you something you wish to ponder is between you and them.

And that paragraph, folks, is the sum total of my skills in delivering the sales pitch that might move 500 people to buy my book, thereby delivering a thousand steps from home to the Canadian bestseller list for poetry. (Yes, our cultural regard for poetry as a viable commercial product in Canada really is that modest.)

The thing I struggled with mightily in the final stages of preparing this book was practical more so than creative, and it had everything to do with assuring the words reflected the Canadian identity of the work. While not all of the poems describe moments related to Canada directly, the thematic whole depended on it being clear the observations were made through Canadian eyes.

There are places where a particular aspect of Canadian societal mindset receives scolding, for example, and it is important to enter into the equation that the criticism is not coming from afield but from “one of us.” Where Newfoundland is similarly called out (or cuddled) I at least had a rich vocabulary of word and imagery cues to draw from in establishing qualification. The Canadian cultural entity has fewer of these.

It came down to Canadian spelling: achieving it on a consistent basis. This was more challenging than you might imagine. There was an array of societal courtesies expecting acknowledgement that caused me less grief.

I didn’t fret a whole lot about achieving gender neutrality in the language, for example, though this work could by no means be accused of being either negligent or regressive. Here is the thinking: while there is a time in which presenting intentional inclusivity in formal communication becomes an element of social decorum, compulsory box-checking risks straining the integrity of the narrative voice — which consistently belongs to me — and, in turn, compromising the legitimacy of the reporting.

I didn’t fuss about (especially where spiritual observations are made) the likelihood of you and I living in houses that are painted different colors, either. As a poet, among the things that catch my attention are changes taking place in perceived constants. The things I notice in my turquoise room, then, might also be true in your lavender (or … gulp! … beige) room. So goes the belief in notetaking in the service of universal truths.

Nor did I tax too many resources in figuring out whether I should develop a sense of racial invisibility when approaching subject matter such as the Black Lives Matter movement. I have legitimate and valuable insight to offer — from my own perspective that I am qualified to make in this form — so the services of no licensing commissioner was deemed necessary.

To explain: The treatment of BLM in this book does not include encouraging participants to tone down the intensity of their action. Neither does it champion the end goals of the cause, nor proclaim a sense of brotherhood that didn’t already exist. Instead, the sober observations I make are not only compatible with but particular to the perspectives my life experiences have molded.

Why mastering Canadian spelling gave me such great angst is rooted in the elusive mystery of just what, exactly, bona fide Canadian spelling is. Agreement on just who would qualify as an authority is difficult to pin down. Borrowing from British or American authorities doesn’t count, because the debate will become lost in arguments about measurement.

I’m an old-school Canadian Press-style adherent (predating its millennium-era makeover, where stylistic bias tilted toward British influence and away from the identity it had forged through a longstanding relationship with the U.S.-based Associated Press). For most of my professional writing through the years the traditional hybrid CP standard was in vogue. It is generally the style used on this website too, since many of my readers and affiliates are border-crossing North Americans, and place of origin is not a critical factor in the communication taking place here. It is not particularly helpful, however, when one is pursuing cultural identity over language efficiency.

Back in the early days of online publishing, I was on the editorial board of independent newspaper groups when developing a distinct Canadian-spelling schema was our response to the facelessness challenging our drive toward a meaningful online presence. We were reasonably successful in establishing identity in this way for newspaper enterprises, but it shocks me now to realize just how imprecise we were in mastering the spelling.

It was the pursuit of this elusive precision, more so than the romanticized vision of the lone poet burning the midnight oil, that kept me laboring into the night in making the final edits for a thousand steps from home.

God love the child anyway!